It’s tough out there, no doubt about it. The headlines are coming in fast and furious, and only a fool would scoff at it all and profess not to be worried. But amid the bad news we have to remind ourselves that investing is a long-term proposition requiring us to go against the grain. Not all the time, that would be exhausting. Just when it matters. And this, of course, is what makes it so hard. Others will be reacting, hollering, “Sell!”, and somehow we have to ignore them, hold firm, and perhaps even offer a measured response of, “Buy.” Not easy.

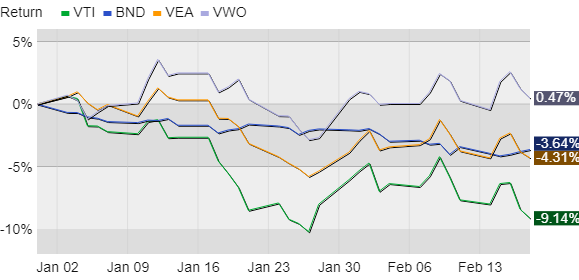

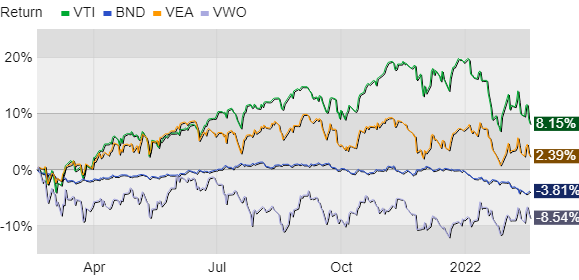

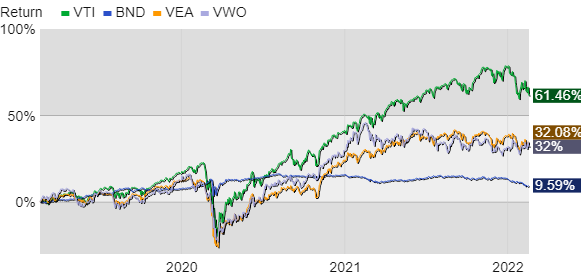

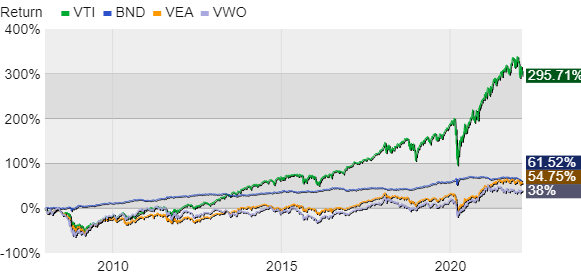

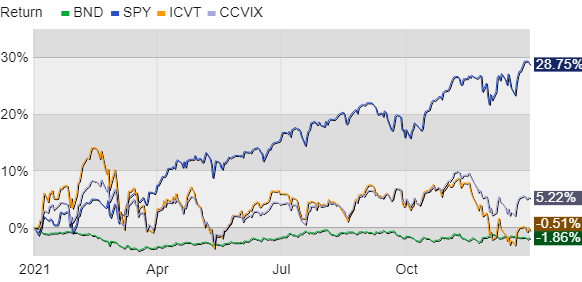

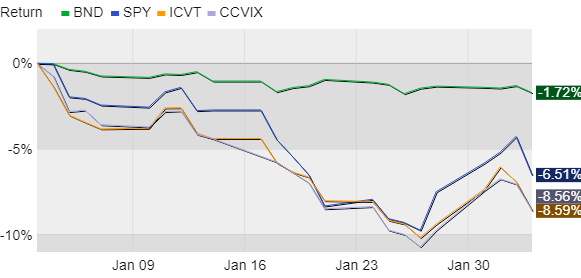

Through yesterday, the S&P 500 is down just shy of 12% so far this year. We’ve dug into gains of the past 12 months, but most diversified investors should be doing better than the broad market. And recency bias is starting to kick in, worsening an already sour mood. But we don’t have to go back far to see the positive returns that now seem like a distant memory to some. The same stock index is up about 59% in the past three years and has nearly doubled in the past five years. Ten years… 270%.

It was easy to be bullish back then, or at least it was in hindsight. Just think of all the events investors had to contend with during those years. Would anyone blithely report being bullish 100% of the time? Of course not. But what did you do about it? Many sold during the numerous lows and were never able to buy back in. Let’s the rest of us hope that with enough time, and enough hindsight, that we’ll be proven right for holding on now just as we have been many times before. Again, that sort of all-weather patience and persistence isn’t easy, nor is it for everyone, but it’s required to be a successful long-term investor.

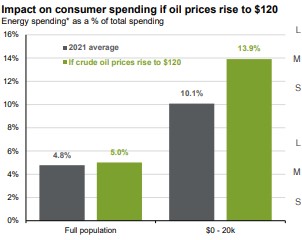

And there’s good news out there too. One example: We’re all aware that oil prices shot up dramatically on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But they've since come back sharply. Bespoke Investment Group reports that the price of West Texas Intermediate (the US oil benchmark) rose over 30% in just over a week earlier this month but has since fallen about 22%, potentially setting up the largest decline from a WTI highpoint over a week ever. Among other things, this illustrates how investor sentiment and market prices can change rapidly, and it goes both ways. Assuming oil stays at these levels, prices at the pump should eventually come down as well. And that would be welcome indeed.

As a helpful reminder of how hard investing can be, and perhaps license to cut ourselves some slack, here’s an excellent article by Jason Zweig of The Wall Street Journal from a few days ago. He packs a lot of truisms into a short piece that’s worth reading a few times. I’m reproducing it here minus the variety of embedded hyperlinks, but a link is below if you’d like to read in full.

In the fall of 1939, just after Adolf Hitler’s forces blasted into Poland and plunged the world into war, a young man from a small town in Tennessee instructed his broker to buy $100 worth of every stock trading on a major U.S. exchange for less than $1 per share.

His broker reported back that he’d bought a sliver of every company trading under $1 that wasn’t bankrupt. “No, no,” exclaimed the client, “I want them all. Every last one, bankrupt or not.” He ended up with 104 companies, 34 of them in bankruptcy.

The customer was named John Templeton. At the tender age of 26, he had to borrow $10,000—more than $200,000 today—to finance his courage.

Mr. Templeton died in 2008, but in December 1989, I interviewed him at his home in the Caribbean. I asked how he had felt when he bought those stocks in 1939.

“I regarded my own fear as a signal of how dire things were,” said Mr. Templeton, a deeply religious man. “I wasn’t sure they wouldn’t get worse, and in fact they did. But I was quite sure we were close to the point of maximum pessimism. And if things got much worse, then civilization itself would not survive—which I didn’t think the Lord would allow to happen.”

The next year, France fell; in 1941 came Pearl Harbor; in 1942, the Nazis were rolling across Russia. Mr. Templeton held on. He finally sold in 1944, after five of the most frightening years in modern history. He made a profit on 100 out of the 104 stocks, more than quadrupling his money.

Mr. Templeton went on to become one of the most successful money managers of all time. The way he positioned his portfolio for a world at war is a reminder that great investors possess seven cardinal virtues: curiosity, skepticism, discipline, independence, humility, patience and—above all—courage.

It would be absurd and offensive to suggest that investing ever requires the kind of courage Ukrainians are displaying as they fight to the death to defend their homeland. But, for most of the past decade or more, investing has required almost no courage at all, and that may well be changing.

Inflation rose to a 7.9% annual rate last month, the highest since 1982, and some analysts think oil prices could hit $200 a barrel.

In early March, Peter Berezin, chief global strategist at BCA Research in Montreal, put the odds of a “civilization-ending global nuclear war” in the next year at an “uncomfortably high 10%.”

In another sign of the times, a 22-year-old visitor to the Bogleheads investing forum on Reddit asked plaintively this week: “I can’t get over the thought that by the age of 60 will earth still be livable? Should I be using [my savings for retirement] somewhere else and live in the ‘now’?”

Yet the S&P 500 has lost less than 1% since Feb. 24, the day Russia launched its onslaught. Over the same period, according to FactSet, more than $770 million in new money has flowed into ARK Innovation, the exchange-traded fund run by aggressive-growth investor Cathie Wood.

That’s a familiar pattern. On Oct. 26, 1962, near the peak of the Cuban missile crisis, The Wall Street Journal reported that “If it doesn’t end in nuclear war, the Cuban crisis could give the U.S. economy an unexpected lift and maybe even postpone a recession.”

From their high in mid-October 1962, U.S. stocks fell only 7% even as the world teetered on the brink of nuclear war.

Nevertheless, a grim era for investing was not far off, in which stocks went nowhere and inflation raged. Had you invested $1,000 in large U.S. stocks at the beginning of 1966, by September 1974 it would have been worth less than $580 after inflation, according to Morningstar. You wouldn’t have stayed in the black, after inflation, until the end of 1982.

That shows two things.

First, glaringly obvious big fears, like the risk of nuclear war, can blind investors to insidious but more likely dangers, like the ravages of inflation.

Second, investors need not only the courage to act, but the courage not to act—the courage to resist. By the early 1980s, countless investors had given up on stocks, while many others had been hoodwinked by brokers into buying limited partnerships and other “alternative” investments that wiped out their wealth.

If it feels brave to you to rush out and buy energy stocks, you’re kidding yourself; that would have been courageous in April 2020, when oil prices hit their all-time low. Now, it’s a consensus trade. Courage isn’t doing the easy thing; it’s doing the hard thing.

Making a courageous investment “gives you that awful feeling you get in the pit of the stomach when you’re afraid you’re throwing good money after bad,” says investor and financial historian William Bernstein of Efficient Frontier Advisors in Eastford, Conn.

You can be pretty sure you’re manifesting courage as an investor when you listen to what your gut tells you—and then do the opposite.

Here’s a link to the article. The Journal has a soft paywall, so let me know if you can’t access the site and I can send it to you from my account.

Have questions? Ask me. I can help.

- Created on .