Recent weeks have seen a whipsawing of expectations for the economy and the path of interest rates. The yield on the 10yr Treasury, a key benchmark, rose to over 4% a few times and interest rates in general have been quite volatile. But the upward path seemed destined to continue as inflation headed higher and the Fed kept raising rates to fight it. Or at least that was the dominant narrative for a while.

Lately, however, expectations have shifted given that inflation has been steadily waning and the economy, for all its pluses, seems headed toward recession. That and recent news of bank failures has pushed more investors into bonds for safety and higher yields, which has pushed the 10yr Treasury yield back below 3.5%. Other investors now think they’ve missed the boat and that maybe they should wait for yields to go back up before buying more. But will rates go back up?

The following article from JPMorgan addresses this and talks about the queasiness some investors feel about bonds given such poor performance last year. That may be true, but we still need to navigate the market we have and not wait for the one we hope for. At least according to JPMorgan, the one we have is this: We’re heading into a recession, the Fed may cut interest rates to spur growth, yields track with what the Fed does, so the bond market offers a good opportunity right now.

That logic seems pretty straightforward but, of course, it’s never that simple. There’s lots of news out there about how this and that indicator always forecasts recession, and many do. But we’ve also never gone into recession when the job market remains this strong. The official unemployment rate is 3.5%, up a tick from a historic low in February.

Maybe we enter a recession, maybe we don’t. Either way, a lot remains to be seen and the outlook and dominant narratives are sure to shift multiple times in the coming months. If nothing else, yields on short-term investments are higher than they’ve been for a long time, so I think it’s wise to put excess cash to work now instead of waiting.

From JPMorgan…

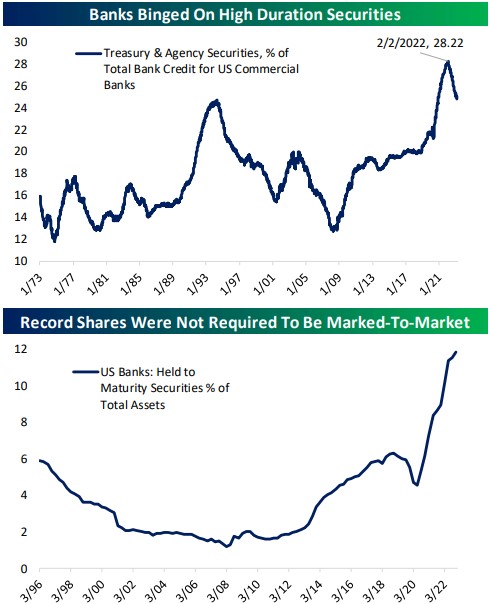

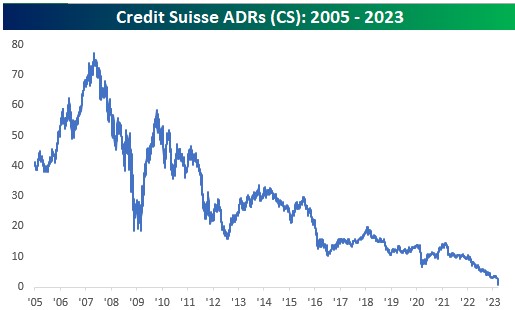

At the start of the year, the term “soft landing” was a common refrain from both policymakers and investors. However, despite the most aggressive Federal Reserve (Fed) rate hiking cycle since the 1970s, growth has remained robust and inflation has moderated. The possibility that central bankers might have managed to thread the needle by bringing down inflation without damaging growth initially pushed recession forecasts out to 2024, but the banking crisis in both the U.S. and Europe has seen a sharp tightening in financial conditions as lenders strike a cautious tone and hold back on extending credit to the real economy. This was reflected in the most recent Senior Loan Officer Survey from the Federal Reserve, which showed a sharp tightening in lending standards to U.S. firms. If credit to the economy is choked off, then the ripple effects from recent bank failures could well pull forward the timing of any recession and potentially bring the Fed’s rate hiking cycle to a premature end.

Following the latest Fed meeting on March 22, the Chair of the U.S. Fed, Jerome Powell, acknowledged that a credit crunch would have significant macroeconomic implications that could potentially influence the trajectory of Fed policy. However, he added that “rate cuts are not in our base case.” Despite the Fed Chair’s comments, market pricing of the pathway for the Fed Funds rate has shifted markedly in the last few weeks. Investors now anticipate that a Fed pause is imminent and that they will begin cutting rates as soon as September 2023 as growth slows and inflation continues to abate.

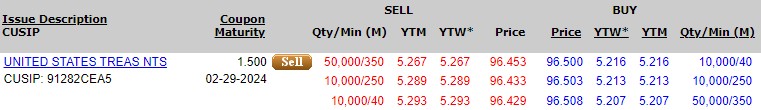

As the Fed ponders its next step, investors should be mindful that the window of opportunity that has emerged in fixed income may slam shut quickly. The yield on the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Index ended March at 4.4%, close to its highest levels in nearly 15-years. However, as shown in the chart below, the yield of the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Index is closely tied to the Fed Funds rate; in prior recessions, as growth has stalled, the Fed has lowered rates and bond yields have quickly followed suit.

After seeing the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Index fall by 13% in 2022 – its worst year on record – it is understandable that some investors may feel queasy at the prospect of jumping back into fixed income markets. However, it is important to remember that the yield of a bond benchmark provides a reasonable estimate of its forward return. As such, with the current yield offered by the bond markets potentially the high-water mark for this rate hiking cycle, investors could be well-served by taking advantage of this opportunity before the window begins to close.

![]()

Here's a link to the article if you’d like to read it in situ.

Have questions? Ask us. We can help.

- Created on .