Deficits and Tariffs

As I'm sure we're all aware, the stock market has been in full blown "react" mode during the past several weeks. While there have been a variety of issues fueling this volatility, the first was interest rates and the second is what some view as a brewing trade war with China. With all the rhetoric bouncing around it's hard not to feel nervous. Anytime the word "war" is used it's bound to ramp up the tension level anyway. So, what's one to do in the face of the current market anxiety? Simply put – stay calm.

Part of staying calm is educating yourself about the issues at hand, all of which take longer to explain than a quick sound bite on the news (and even this blog post). Global trade is incredibly complicated, and I don't claim to be an expert in this area. Part of what makes the topic complicated is that the big picture themes make sense, but the details are often counterintuitive.

Take the concept of a having a trade deficit with another country. We buy things from another country and they buy from us (bilateral trade). If we buy more from them than they do from us, that's a deficit. The opposite yields a surplus. This makes sense but of course there's more to it than that and in this kind of thing the details are important.

The concept of "deficit" gets bandied about in the media and is often equated with "deficiency", implying that having a trade deficit with another country somehow makes the US weak or, well, deficient. While such deficiencies might make for an interesting rant on cable news, it's not the whole story.

If you dig deeper, you'll quickly see how interconnected and complicated the global economy is and how it defies soundbites. For example, we might ship product components (from the US or elsewhere) to another country where they are assembled and shipped back. Some or all the components might come from other countries as well, each going into the product that is "Made in China" but sold on our shelves. But how much is Chinese versus US versus Vietnamese versus German...? These numbers get muddied when wrapped up in the headline trade numbers.

Take this explainer from www.econofact.org about the iPhone as an example:

The iPhone offers a particularly illuminating example of how international supply chains cause a mismeasurement of true bilateral trade. iPhones are assembled and tested in China. For instance, each iPhone 7 32GB imported into the United States is recorded as a $225 import from China, since this is its manufacturing cost (the consumer unsubsidized price is $649, which reflects Apple's marketing, design, and engineering costs as well as its profit margin). Out of this $225, only $5 represents work performed in China, which is almost exclusively assembly and testing. The remaining $220 represents the cost of components, which are overwhelmingly produced outside of China, and then exported to China for assembly. Components come from throughout Asia (Korea, Japan, and Taiwan are the largest suppliers), as well as Europe, and the Americas. Thus, the $225 recorded import from China embodies U.S. imports from many other countries and should not be used to measure the extent of the bilateral trade deficit between the U.S. and China for this good.

While nobody doubts that we buy more stuff from China than they buy from us, China also buys a lot of our services. And the trade of services is tracked separately from goods. According to the US International Trade Commission, we have a surplus with China when it comes to a variety of services such as travel, professional services, and "charges for the use of intellectual property" by the Chinese. Presumably, as China continues to open its economy these services will be in greater demand, potentially leading to a larger services surplus.

When taken together, we still have a trade deficit with China but it's smaller than the deficit on "goods" alone. In February, our combined deficit was about $58 billion, including a $77 billion deficit in goods and a $19 billion surplus in services, according to the US Census Bureau and the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

So, we're obviously growing more deeply connected economically to China (and other large economies) as time goes by. This is in some ways uncomfortable but, frankly, it's hard to imagine that changing, even with the recent tariff and trade war rhetoric. Governments use tariffs in an attempt to rebalance changes stemming from globalization, but they're blunt tools often used in a reactionary way. It is simply not possible (or desirable?) for a product like the iPhone to be designed and manufactured 100% in California, or Kentucky, for that matter. The global economy has moved beyond that, something most people understand, even if the details of how and why remain elusive.

It could very well be that the proposed tariffs are a hardline stance or just negotiating tactics, as the Trump Administration has confusingly stated in recent days. Time will tell. But in the meantime, we get to deal with the associated market volatility. It's just one more example of how hard it sometimes is being a long-term investor. If it were easy, anyone could do it, right?

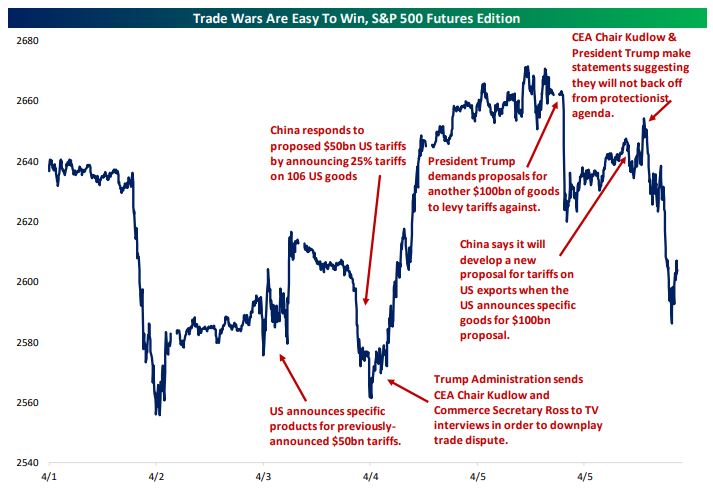

To give you an idea of how investors reacted to tariff news last week, look at the following chart from Bespoke Investment Group. Markets were up on softer tariff news yesterday and again this morning, but still with no substantive changes.

http://econofact.org/what-do-we-learn-from-bilateral-trade-deficits

Have questions? Ask me. I can help.

- Created on .