News in recent weeks has shed a brighter light on how important liquidity is to our financial success. Lots of people, even the folks who run banks, can think they have more liquidity than they actually do because they’re counting an asset as liquid when it really isn’t.

Like I mentioned recently, liquidity is generally defined as how quickly and cheaply we can access money when needed. Cash in the bank is liquid and safe assuming deposits are within the limits of federal deposit insurance. Investments in heavily traded stocks and bonds, or common funds that own them, are also considered liquid because you can sell them quickly and often with no transaction fee. You can lose money on stocks and bonds if you have to sell at the wrong time, but good planning can help with this – the point being that this money is gettable without restriction, making it liquid.

Some of our largest assets, like our home, our car, boat, or maybe original artwork aren’t liquid. We can usually sell these assets, but doing so takes time and money to get a fair price. All of us have a mix of liquid and illiquid assets and there’s nothing wrong with that – striking the right balance is key and this is where people can get into trouble.

Another common type of illiquid asset is an annuity contract. We’ve discussed these at some length before. The simplest type is buying future income – you trade a lump sum today for regular income lasting X years, or maybe the rest of your life. You pay a present value for that future income stream and the annuity company, on it’s own, promises to keep paying. That’s pretty simple and there are valid reasons why one would seek out something like this.

Annuities quickly get more complicated from there and, quite honestly, should be avoided. There are numerous reasons for this as well, but one that’s top of mind this morning is how annuities are said to be sold and not bought, that a salesperson needs to convince a customer of an annuity’s virtue because you’d never buy it on your own – it would quickly fail the sniff test.

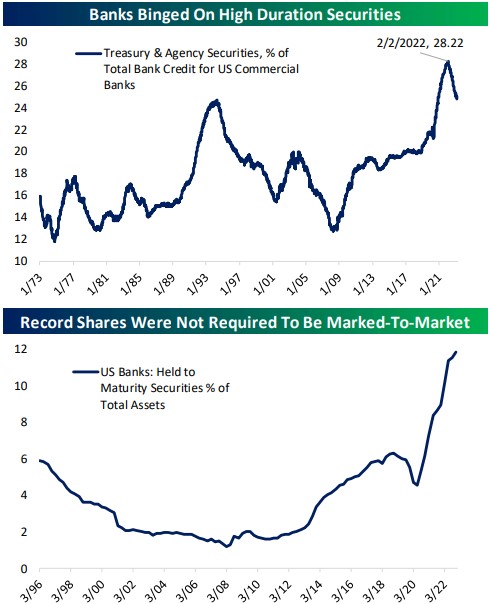

The problem, of course, is that there are thundering hordes of salespeople incentivized to push this stuff all day long and lots of people end up buying. They fall for “guaranteed” and “high rate of return” and fail to realize, often because they’re never told (shown deep within a 90-page disclosure doesn’t count) that the salesperson is receiving a fat commission on the sale and how that commission grows as the purchase amount grows and the annuity terms get worse, and how the alluring guarantee is only as good as the insurance company’s health which, as with certain regional banks of late, can change rapidly.

At issue this morning is an update to a string of excellent reporting by The Wall Street Journal about a Yale-educated financier and the thousands of annuity contract owners left in a lurch after the shell game he seems to have been running began imploding. $2.2 billion worth of accounts are frozen and, unfortunately, that leaves lots of folks waiting on lengthy court battles.

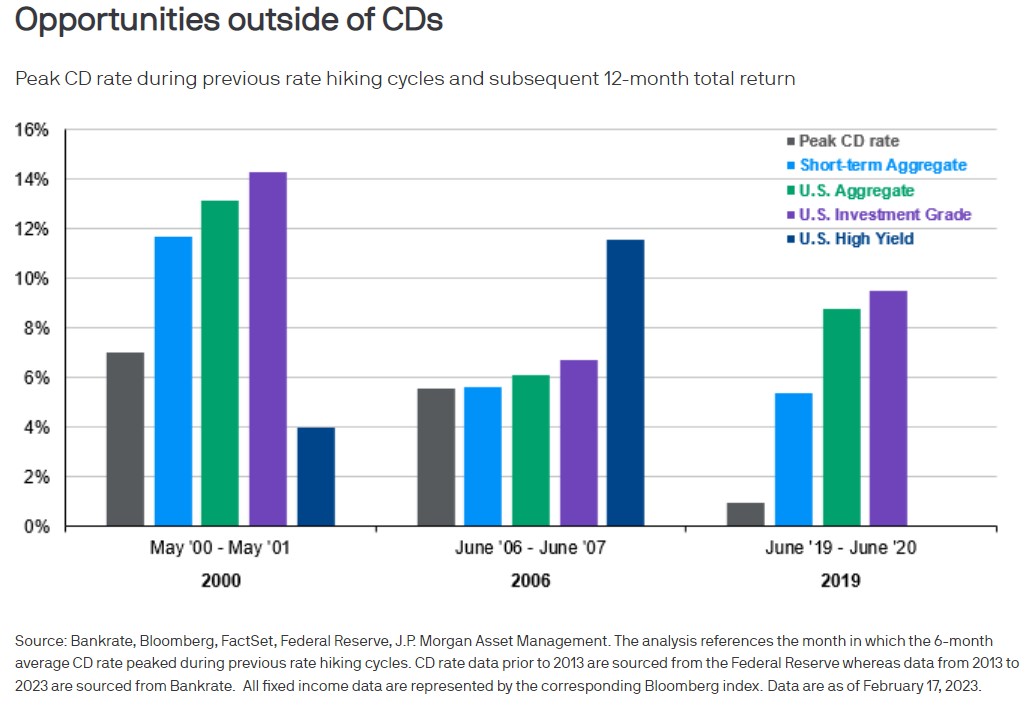

If you read these stories you’ll notice one throughline being how the investor’s “financial advisor at their local bank” (that combo alone should be a red flag) told them how “safe and easily accessible” these contracts were and how it was a smart investment since bank CDs were yielding less. The investors were often talked into putting too much of their liquidity into these more complicated forms of annuity, another common problem, and are now suffering the consequences. I hate reading stuff like this. How can we know so much and yet learn nothing? Maybe a third of your money into illiquid assets, but more than that and you’re asking for trouble.

These stories and the innerworkings of the sales organizations that peddle these products are a big reason why I started my firm nearly ten years ago. Back then I resolved, among other things, to never ever get clients into a liquidity crunch by putting their money into fundamentally illiquid investments while leading them to believe how liquid they were. It’s a horrible abuse of trust by people who should have known better. (That many of the salespeople are specifically trained not to know, to have a form of plausible deniability, is an ongoing issue in my industry and we can save those details for another day.)

So maybe view all this as a cautionary tale about putting too many eggs into one basket and, if you will, the power of trust and how easily abused it is.

Here's a link to the piece I mentioned. Let me know if you get blocked by the WSJ’s paywall and I can send it to you from my account.

Have questions? Ask us. We can help.

- Created on .