With all the recent market volatility I thought it would be interesting to lift the curtain a bit on one aspect of how I manage client portfolios, my rebalancing process. This might provide some insight and perhaps some reassurance if I’m managing your investments, or perhaps a bit of help if you’re managing things on your own.

First let me say that setting up and managing a portfolio of investments entails both art and science. There are also tons of details to get your arms around and most are in constant flux. I have to think about the markets, the outlook, taxes, brokerage firm mechanics and expenses and, above all, what the client needs. None of this guarantees success. Instead, portfolio management is fundamentally an exercise in trying to control what can be controlled regardless of what the markets throw at us.

So hopefully without getting too deep into the weeds, let’s jump right in.

Everything I do for my clients is custom and based on factors such as:

General needs – Maybe the client needs retirement income or is trying to accumulate money for retirement. Sometimes, perhaps ironically, it’s both at the same time with the added kicker of wanting to preserve as much money as possible for beneficiaries.

Tax situation – I’ll often build portfolios around concentrated positions that would create a large tax bill if sold arbitrarily. It’s also common that clients need their income to be as tax-efficient as possible. Both requirements end up complicating portfolio construction and put added emphasis on so-called asset location. This is especially true when clients have IRAs, Roth IRAs, non-retirement “brokerage” accounts, and maybe college accounts for their kids and grandkids too; each are subject to different tax rules and should be invested accordingly.

Personal preferences – Sometimes clients want to emphasize (or deemphasize) certain industries or even particular companies in their portfolios. The process for getting this done has evolved a lot in the nearly 20 years I’ve been doing this work and software helps a great deal.

Risk tolerance and capacity – Each of us has our own tolerance for investment risk but we should also understand our capacity for taking it on. The first is psychological while the second is, or at least ought to be, purely financial. Sometimes the two align but often they don’t. The result tends to be a sometimes-tenuous balance between taking enough risk to achieve the returns I know the client needs but not so much risk that I set the client up for failure in a volatile market. And it doesn’t always work.

I have a variety of tech at my disposal to automate the investing process and lots of others in my industry simply farm this work out to third parties. “Freemium” and ultra-low-cost cookie-cutter services are clicks away. But opportunities can get lost in the rush to make everything easier. While there certainly are some similarities between Clients A, B, and C, the differing details of each person’s situation are plentiful and meaningful enough that investment models, and the work I do in general, should be custom.

A client’s model is essentially a list of investments chosen by me to a fill a specific need within the portfolio. Each investment has its own weighting and I put this into fancy software to analyze the model and tweak things until it’s just right. I make decisions about investment income, expenses, exposure to domestic versus foreign stocks, short- versus medium-term bonds, and so forth. There’s a laundry list of analytical stuff that I won’t bore you with here.

Once the model is set up I send it to my rebalancing software. From there I don’t just push a button and let an algorithm buy and sell on a client’s behalf. Instead, I set and monitor target ranges around each investment in a client’s account. For example, let’s say I want 12% of a portfolio invested in the Vanguard High Dividend Yield ETF, ticker symbol VYM. The software flags me when the target weighting has dropped by 10%, 15%, 20%, or whatever I want. If the position has grown too much the software recommends selling some to bring it back within range. And since growth in one area naturally means loss in another, the software also points out investments that are at the low end of their target range. This is rebalancing at the micro-level whereas most people go macro by just looking at their overall exposure to stocks and bonds assuming they rebalance at all.

Each week I go through all the portfolios I manage but during volatile times like these it can be daily. This higher frequency is mostly to monitor things as closely as possible and doesn’t mean that I buy and sell every day. In fact, it’s often about what I don’t do, what I don’t buy and sell, that can make a positive difference for clients. That’s one reason why the thresholds are ranges and not 0% - portfolios should be allowed to move around with the markets so long as the range is controlled.

As I monitor the rebalancing process I’m also scrutinizing each investment to ensure it’s still high quality, low cost, and continues to fit within the portfolio. Since I’m unconstrained in what I can buy for clients I’ll swap an investment out if needs be, or I can move things around for tax-loss harvesting.

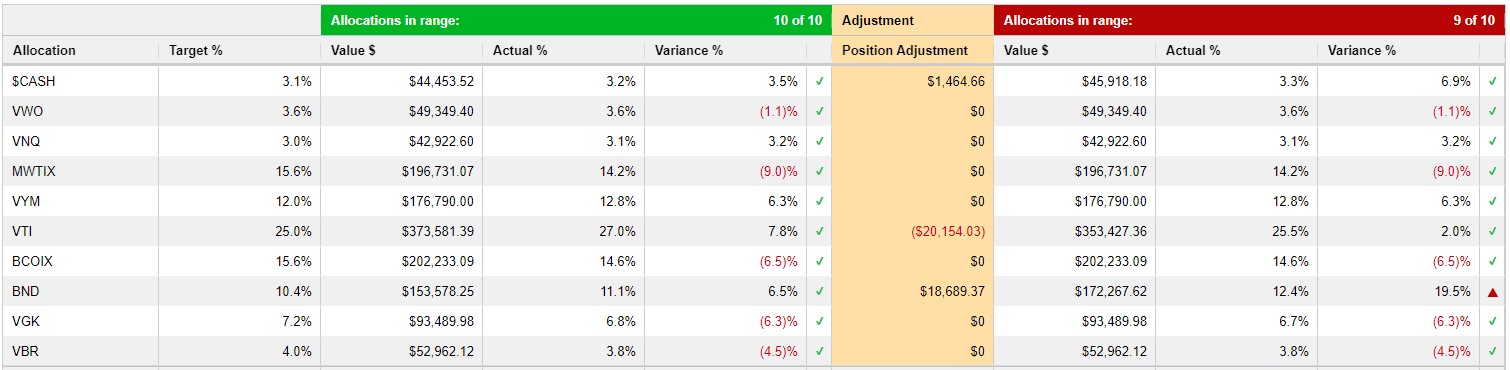

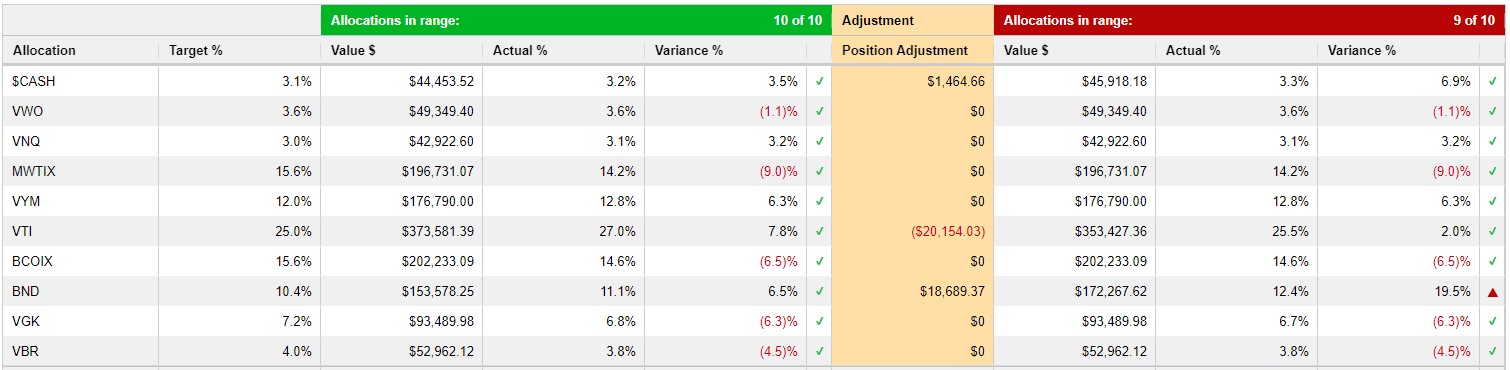

Here’s part of a screen showing an actual model from yesterday. The investment ticker symbols are on the left followed by my target weightings, actual (current) weights, and variance. We see the software’s recommendations in the yellow column and on the right we see what the portfolio would look like if I said yes to everything. That’s the big picture. Then I consider the client’s situation.

This client has ample cash in their portfolio (and in their bank account) and the 3.5% variance is fine, so we’ll leave that alone. No other variances are beyond even 10%, so we’re good there for now. However, lately I’ve been buying Vanguard Total Stock Market, ticker symbol VTI, and the client’s exposure has inched up with the market. Should it continue to climb I’ll be looking to trim it back and give sale proceeds to bonds via tickers MWTIX, BCOIX, potentially to foreign stocks via VGK, or all three. You may notice how the software is recommending I go up to 19.5% variance on BND, another bond fund. That’s because I put a cap on MWTIX and told the software to recommend BND instead. There are all sorts of fun customizations like that.

All this helps a client’s bottom line over time, and I could go on but let’s leave it there for today. Stocks finally had a good run last week and we saw some decent follow through yesterday. Even though markets finished in the red, it was by a small fraction and, given all the recent volatility, I’ll take it.

Have questions? Ask me. I can help.