There’s a perplexing dynamic playing out between how people feel about their own financial situation compared to how they see everyone else’s. This shows up in private conversation and in national surveys where people report feeling pretty darn good about their own finances while also reporting that the world around them seems to be falling apart a little more each day. Maybe these two things (positive me, negative you) can exist simultaneously but it’s hard to imagine them doing so at extremes for very long.

This appeared in two different places recently and I wanted to share some snippets with you. First, the Federal Reserve updated its annual Fall survey last month for 2021. They’ve been doing so since 2013. Second is a monthly survey conducted by my research partners at Bespoke Investment Group, in this case the data goes back to 2014.

The Fed’s survey found that Americans, at least on average, were doing quite well last Fall. Their personal financial well-being had improved from 2020 which, as the report suggests and makes intuitive sense, ties into the ongoing economic recovery from the pandemic and many months of government money flowing into lots of households. Accordingly, more Americans reported being able to pay cash to cover a relatively small, unexpected bill, whereas even pre-pandemic they would have needed to whip out their credit card.

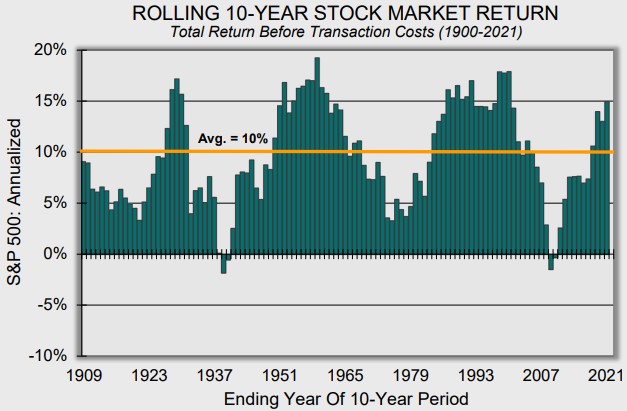

But amid this positive, even rosy, assessment lurked the glaring and perplexing issue The Atlantic recently called the “everything is terrible but I’m fine” perception gap. The piece suggested that this could simply be part of human nature, that we’re wired to be “individually optimistic and socially pessimistic”. If that’s true I don’t pretend to know why. Maybe it’s obvious to you but the gap exists and, at extremes, can have real world implications for the economy and, by extension, the markets. This is especially true when negative sentiment gets overblown.

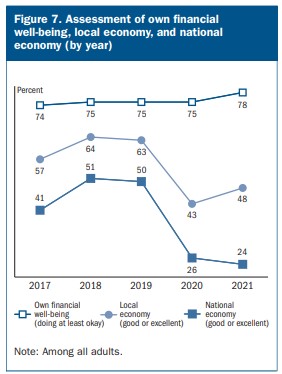

Here's a chart and a few sections from the Fed’s report and a link to the whole thing is below if you’d like to read more.

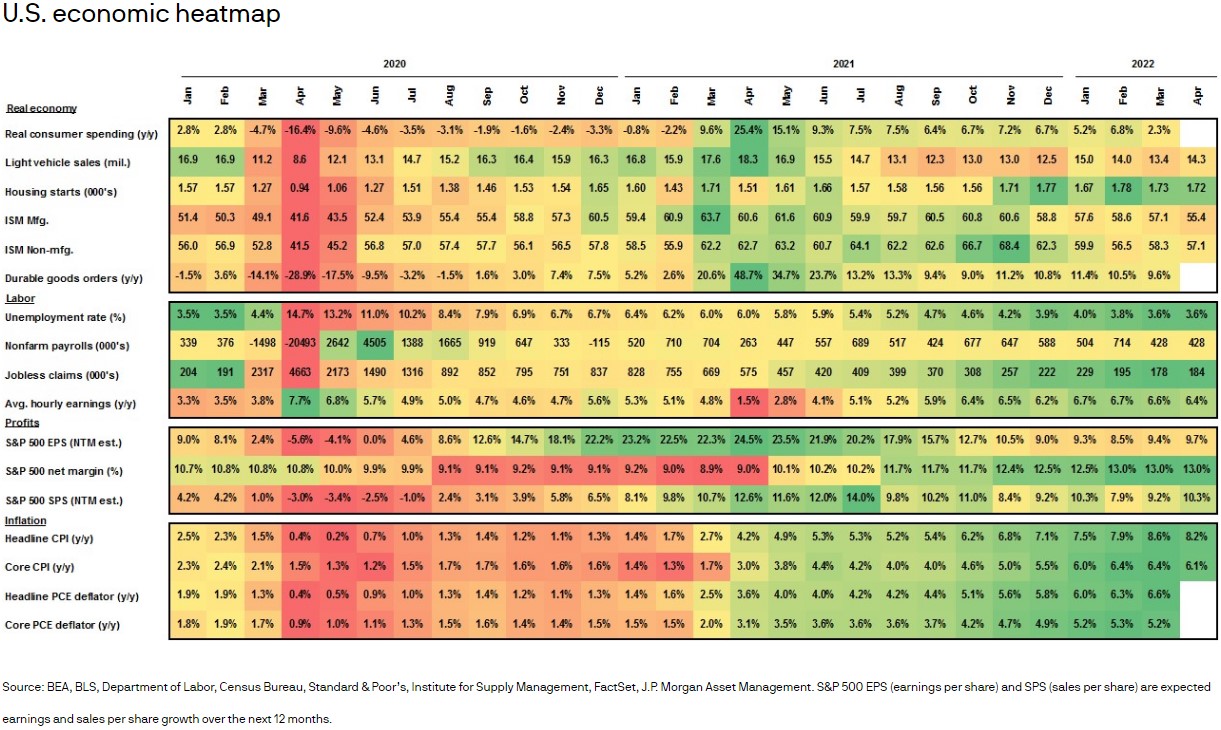

… Despite persistent concerns that people expressed about the national economy, the survey highlights the positive effects of the recovery on the individual financial circumstances of U.S. families.

In 2021, perceptions about the national economy declined slightly. Yet self-reported financial well-being increased to the highest rate since the survey began in 2013. The share of prime-age adults not working because they could not find work had returned to pre-pandemic levels. More adults were able to pay all their monthly bills in full than in either 2019 or 2020. Additionally, the share of adults who would cover a $400 emergency expense completely using cash or its equivalent increased, reaching a new high since the survey began in 2013…

… In the fourth quarter of 2021, the share of adults who were doing at least okay financially increased relative to 2020. With these improvements, overall financial well-being reached its highest level since the survey began in 2013.

Seventy-eight percent of adults were either doing okay or living comfortably financially, the highest share with this level of financial well-being since the survey began in 2013.

Forty-eight percent of adults rated their local economy as “good” or “excellent” in 2021. This share was up from 43 percent in 2020 but well below the 63 percent of adults who rated their local economy as “good” or “excellent” in 2019, before the pandemic…

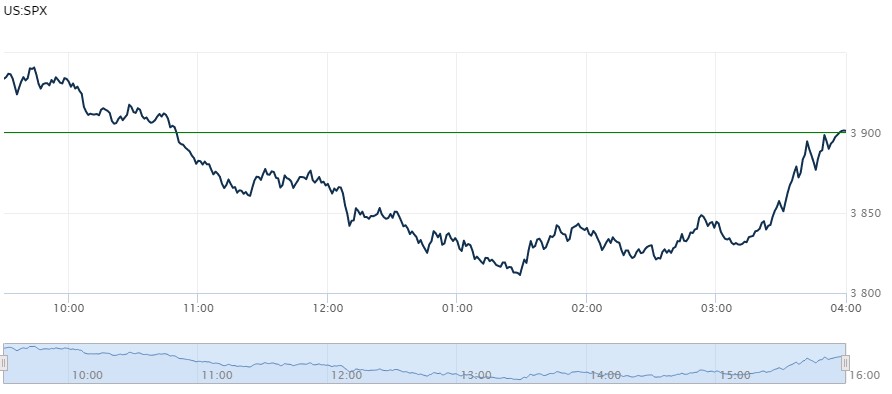

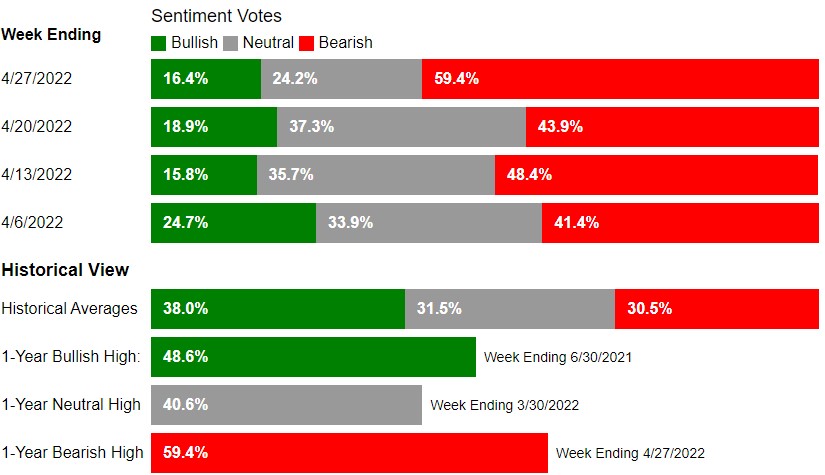

The Fed survey was conducted last Fall before inflation flared up, before Russia invaded Ukraine, and before the stock and bond markets had one of their worst starts to a year ever. So if the survey was done now it might look something like Bespoke’s results below: declining personal confidence and the perception gap widening even faster.

From Bespoke…

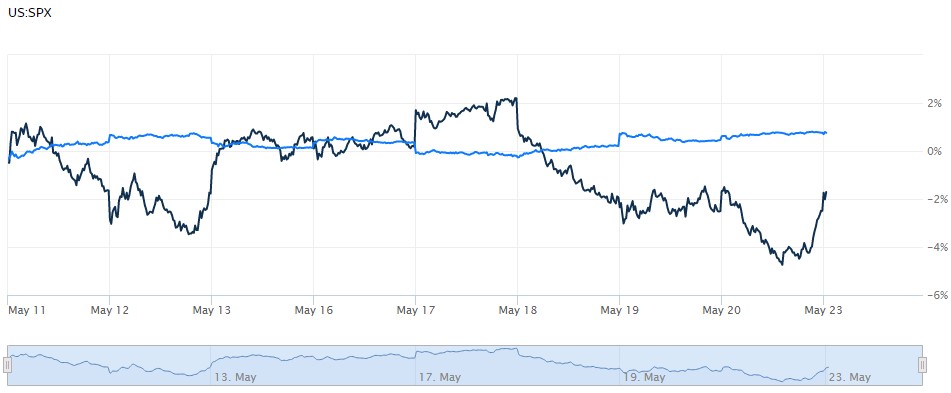

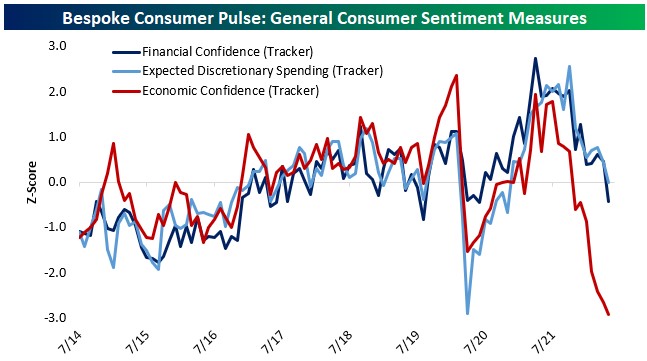

Consumers are extremely negative on the US economy in general. As shown below, economic confidence is a full standard deviation below the previous record low for the data dating back to July of 2014. Typically, general economic confidence is consistent with confidence in consumers' personal finances and expected spending on discretionary items, but over the past year the disconnect has gotten truly enormous. While confidence in personal finances and expected spending are basically at average levels, economic confidence has continued to plunge.

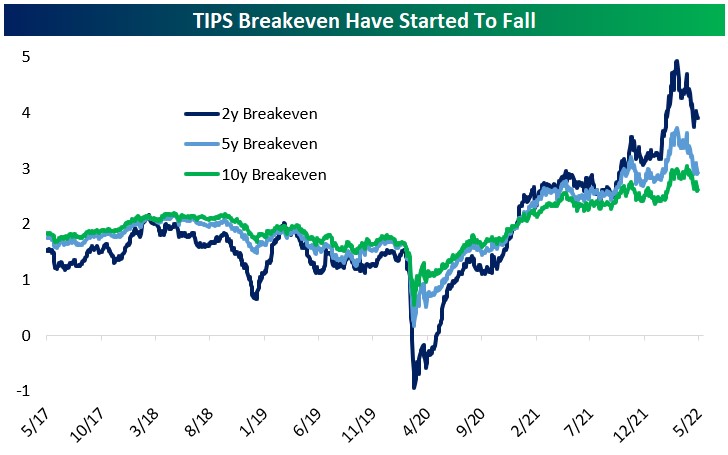

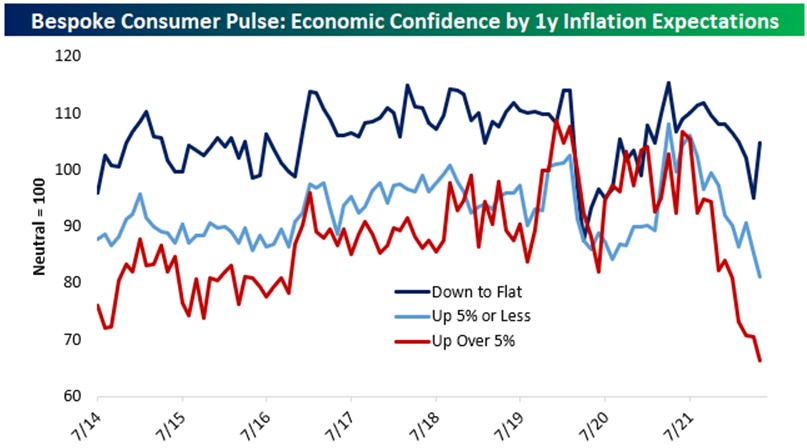

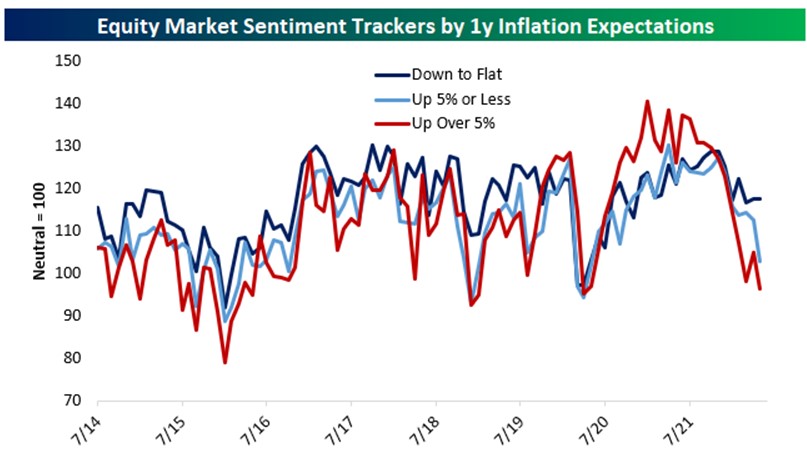

The reason for the collapse in economic confidence is inflation. In the chart below, we show economic sentiment over time by category of inflation expectations. Consumers that expect deflation are by far the most optimistic about the economy, while those who expect manageable inflation (up 5% or less) are more negative. Consumers that expect high inflation over 5% have seen sentiment collapse deep into negative territory. The bottom line: the higher consumers expect inflation to get, the worse they feel about the economy.

Inflation concerns have caused extremely negative sentiment readings, and it's hard to imagine these readings getting too much worse as there's a floor in terms of how low they can go. Therefore, barring a significant negative shift in the economy, this would suggest a higher likelihood of positive surprises (lower rate of inflation) than downside surprises at this point, and any cooling on the inflation front should result in a bounce-back for sentiment (and potentially the stock market).

Here’s a link to the Fed’s paper.

And here’s a link to the opinion piece from The Atlantic on this issue.

Bespoke Investment Group is a subscription-based service, but you can follow them on the socials for free.

https://www.bespokepremium/interactive

Have questions? Ask me. I can help.

- Created on .